20 April 2007 Cultural Identity in Making

Place: Cultural Identity in Making

1. Place and Identity:

(Reference- Tim Cresswell, Place: A Short Introduction; Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History)

-Place: all spaces that people have made meaningful; all spaces people are attached to in one way or another. Space is meaningful location.

-Three fundamental aspects of place as a “meaningful location” (John Agnew):

-Space vs. Place: space is a more abstract concept than place. Spaces have areas and volumes. Space have been seen in distinction to place as realm without meaning. When humans invest meaning in a portion of space and then become attached to it in some way it becomes a place.

-Place vs. Landscape: landscape referred to a portion of the Earth’s surface that can be viewed from one spot. In most definitions of landscape the viewer is outside of it, and this is the primary way in which it differs from place. Places are very much things to be inside of it. As a viewer, we do not live in landscapes, we look at them, and we only live in a place as an inhabitant.

-Place as a Way of Understanding: place is not just a thing in the world but a way of understanding the world. Place is a way of seeing, knowing and understanding the world. When we look at the world as a world of places, we see attachments and connections between people and place, and we see worlds of meaning and experience.

-Production of Place: places are not finished products; instead, they are very much in process. Places are created by cultural practices such as literature, film and music (in short, representation), but most places are more often the product of everyday practices.

“I brought a picture with a frame and put it on the wall. Prior to this, all four walls were bare. I did this without telling them because I thought that since I paid for this room, I should be allowed to do something about it. So I arranged the room, put furniture and TV (the way I wanted them). I would leave the door open so that they (my employers) could see what’s in my room, that it’s not dull anymore.” (Mhay’s words (a Filipina contract worker in Vancouver), quoted by Geraldine Pratt)

-Places are never finished but produced through the repetition of seemingly mundane activities on a daily basis (order of everyday life).

-Everyday life appears to be a personal thing, but it is also social. People often acquire a sense of place in a particular community, and in turn people are connected (or believe themselves to be connected) through the sense of place; consequentially, a particular cultural identity is constituted.

-But places are also sites of contestation. Thus, the question concerning place is a political question. While people fight for places, they construct and maintain places as well.

-Henri Lefebvre, the French philosopher argues that every society has shaped a unique social space that meets its intertwined requirements for economic production and social reproduction. Lefebvre suggests that the production of space is essential to the inner workings of the political economy.

-Lefebvre emphasized the importance of space for shaping social reproduction. One of the consistent ways to limit the economic and political rights of groups has been to constrain social reproduction by limiting access to space.

-Examples:

Exclusion of Japaness Americans from a residential neighbourhood in Hollywood, California

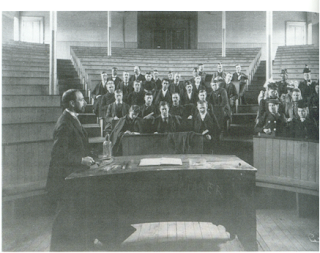

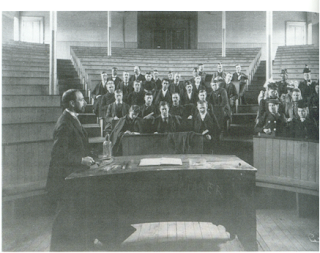

Male and female students sitting separately at a lecture on physics, University of Michigan School, late 1880s

Male and female students sitting separately at a lecture on physics, University of Michigan School, late 1880s

Cognitive maps of Los Angeles as perceived by predominantly Anglo American residents of Westwood, predominantly African American residents of Avalon, predominantly Latino American residents of Boyle Heights (The Visual Environment of Los Angeles, Los Angeles Department of City Planning, April 1971, pp.9-10)

Cognitive maps of Los Angeles as perceived by predominantly Anglo American residents of Westwood, predominantly African American residents of Avalon, predominantly Latino American residents of Boyle Heights (The Visual Environment of Los Angeles, Los Angeles Department of City Planning, April 1971, pp.9-10)

-「職工盟帶過天水圍街坊”出城”,發覺她們連幾條主要隧道的名字都不知道。在文化認同上,她們只是一個” 天水圍人”,不是”香港人”」(陳惜姿﹕《天水圍12師奶》,頁159)

-Questions: how cultural identity and cultural politics of identity are constructed and shaped through the creation of meanings in place? Is it possible to intervene the cultural politics of identity through the production and technology of place?Through the preservation or constitution of social/public memories.

-One of the ways in which memories are constituted is through the production of place. Monuments, museums, the preservation of particular buildings and the promotion of whole urban neighbourhoods as “heritage zones” are all examples of the placing of memory. The very materiality of a place suggests that memory is inscribed in the landscape as public memory. Place is the realm of history-in-place.

2. Vietnam Veteran's Memorial(1982) by Maya Ying Lin (林瓔):

(Reference- Maya Ying Lin, Boundaries; Freida Lee Mock, Maya Lin - A Strong Clear Vision (DVD, 1995))

- Although administered under National Parks Service of the Federal Government, VVM was built in 1982 through the impetus of a group of Vietnam Veterans, who raised the funds and negotiated for a site on the National Mall in Washington.

-Situated on the grassy slope of the Constitutional Gardens nears the Lincoln Memorial, the memorial consists of two polished black walls of granite set into the earth at an angle of 125 degrees. The walls form an extended V almost 500 feet in length, tapering in both directions from a height of approximately ten feet at the central hinge. These walls inscribed with 58132 names of men and women who died in the war. The framing dates of 1959 and 1975 are the only dates listed on the wall; the names are listed alphabetically within each “casualty day”, though those dates are not noted.

-Virtually all of the national memorials and monuments in Washington are made of white stone and are constructed to be seen from a distance. In contrast, the VVM cuts into the sloping earth: it is not visible until one is almost upon it. The walls reflect the Washington Monument and the face of the Lincoln Memorial, but they are not visible from the base of either of those structures.

-Before it was built, the memorial was seen by many veterans and critics of modernism as yet another abstract modernist work that the public would find difficult to interpret. But they simply ignored fundamental aspects of this wall. It is not simply a flat, black, abstract wall: it is a wall inscribed with names. When the public visits this memorial, they do not go to see long walls cut into earth but to see the names of those whole lives were lost in the war. Hence, to call this a modernist work is to privilege a formalist reading of its design and to negate its commemorative and textual functions. While modernism in sculpture has been defined as a kind of “site-less-ness,” the memorial is specially situated within the national context of the Mall: the black walls mirror not only the faces of viewers but also the Washington obelisk, thus forming a pastiche of monuments.

-Before it was built, the design of the memorial was under attack not only because of its modernist aesthetics but because it violated implicit taboos about the remembrance of wars. When its design was first unveiled, it was condemned as a highly political statement, a monument to defeat. One Veteran of VVMF read it black walls as evoking “shame, sorrow, degradation of all races”; others perceived its refusal to rise above the earth as indicative of defeat.

-The primary aspect of the memorial that is responsible for the accusation that it does not appropriately remember war is its antiphallic presence. By “antiphallic”I do not mean to imply that the memorial is somehow a passive or feminine form but rather that it opposes the codes of vertical monuments symbolizing power and honour. The memorial does not stand erect above the earth, it is continuous with the earth. The shape of V has been interpreted as V for Vietnam, victim, victory, veteran, violate, valor. Yet, one also finds here a subtext in which the memorial implicitly evokes castration. The V has been read as a female V, reminding us that a “gash”is not only a wound but slang for the female genitals. To its critics it symbolizes the open, castrated wound of this country’s venture into an unsuccessful war.

-At the time the designer of the memorial was chosen anonymously by a group of eight male experts, Maya Lin was a twenty-one-year-old undergraduate at Yale University. She was not only young and incredential, but Chinese-American and, most importantly, female. Eventually, Lin was defined not as American but as “other”. The otherness became an issue not only in the way she was perceived in the media and by some of the veterans, it became a critical issue of whether or not that otherness had informed the design itself

-Trouble between Maya Lin and the veterans began almost immediately. The initial response to Lin’s design was so divided that it eventually became clear to the veterans of the MF that they had either to compromise or to postpone the project. At the end, a plan was devised to erect an alternative statue and flag close to the walls of the memorial, and realist sculptor Frederick Hart was chosen to design it. It was erected in 1984, consists of 3 solders – one black and two white – standing and looking in the general direction of the wall.

- The Name: the chronological listing of names on the VVM provides it with a narrative framework. Read chronologically, the names chart the story of the war. As the names listed alphabetically within a casualty day swells, the intensity of the war is told.

-The incommunicability of the experience of the Vietnam War has been a primary narrative in the Vietnam veterans’discourse. It was precisely this incommunicability that rendered the construction of the VVM necessary. It was due to the fact that, the veterans had been invisible and without voice before the VVM’s construction and the subsequent interest in discussion of the war. Unlike WWII veterans, Vietnam veterans did not arrive home en masse for a celebration but one by one, without any welcome. They were marginalized in the society.

-Within the veterans’ community another group is struggling against an imposed silence: the women veterans. Upon their return, these women were not only subject to the same difficulties as the veterans but were also excluded from the veteran community. Thus, several of these women raised funds to place an intentionally apolitical statue of a woman near the VVM. In August 1990, a design competition for the memorial, to be located just south of the wall, was announced. It’s Hart’s statue that the absence of women so visible make them initiate the project.

- The VVM has been the subject of an extraordinary outpouring of sentiment since it was built. It is presently the most visited site on the Washington Mall. The memorial has taken on all of the trappings of a religious shrine – people bring personal artefacts to leave at the wall as offering. This rush to embrace the memorial as a cultural symbol reveals not only the relief of voicing a history that has been taboo but also a desire to re-inscribe that history. To the veterans, the wall is an atonement for their treatment since the war; to the families and friends of those who died, it is an official recognition of their sorrow and an opportunity to express a grief that was not previously sanctioned; to the others, it is either a profound antiwar statement or an opportunity to rewrite the history of the war to make it fit more neatly into the master narrative of American imperialism. The Memorial’s popularity must thus be seen as an integral component of the recently emerged Vietnam War nostalgia industry. (it transform guilt into duty and pride)

-As the healing process of the Vietnam War is transformed into spectacle and commodity, a complex nostalgia industry has grown.

- The National Park Service is now compiling an archive of the materials left at VVM. Originally, the Park Service classified the objects as “lost and found”. Later, it realized that the objects had been left intentionally, and they began to save them. The objects thus moved from the cultural status of being “lost”to historical artefacts.

- The subject of memorial is not limited to Vietnam War, the objects related to issues such as AIDS, homosexual, Gulf War had also been left at VVM.

1. Place and Identity:

(Reference- Tim Cresswell, Place: A Short Introduction; Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History)

-Place: all spaces that people have made meaningful; all spaces people are attached to in one way or another. Space is meaningful location.

-Three fundamental aspects of place as a “meaningful location” (John Agnew):

- a. location: fixed objective co-ordinates on the Earth’s surface;

- b. locale: material setting for social relations, actual shape of place within which people conduct their lives as individuals, the concrete/material form of a place. Places are material things.

- c. Sense of place: subjective and emotional attachment people have to place, the feeling of “to be there”.

-Space vs. Place: space is a more abstract concept than place. Spaces have areas and volumes. Space have been seen in distinction to place as realm without meaning. When humans invest meaning in a portion of space and then become attached to it in some way it becomes a place.

-Place vs. Landscape: landscape referred to a portion of the Earth’s surface that can be viewed from one spot. In most definitions of landscape the viewer is outside of it, and this is the primary way in which it differs from place. Places are very much things to be inside of it. As a viewer, we do not live in landscapes, we look at them, and we only live in a place as an inhabitant.

-Place as a Way of Understanding: place is not just a thing in the world but a way of understanding the world. Place is a way of seeing, knowing and understanding the world. When we look at the world as a world of places, we see attachments and connections between people and place, and we see worlds of meaning and experience.

-Production of Place: places are not finished products; instead, they are very much in process. Places are created by cultural practices such as literature, film and music (in short, representation), but most places are more often the product of everyday practices.

“I brought a picture with a frame and put it on the wall. Prior to this, all four walls were bare. I did this without telling them because I thought that since I paid for this room, I should be allowed to do something about it. So I arranged the room, put furniture and TV (the way I wanted them). I would leave the door open so that they (my employers) could see what’s in my room, that it’s not dull anymore.” (Mhay’s words (a Filipina contract worker in Vancouver), quoted by Geraldine Pratt)

-Places are never finished but produced through the repetition of seemingly mundane activities on a daily basis (order of everyday life).

-Everyday life appears to be a personal thing, but it is also social. People often acquire a sense of place in a particular community, and in turn people are connected (or believe themselves to be connected) through the sense of place; consequentially, a particular cultural identity is constituted.

-But places are also sites of contestation. Thus, the question concerning place is a political question. While people fight for places, they construct and maintain places as well.

-Henri Lefebvre, the French philosopher argues that every society has shaped a unique social space that meets its intertwined requirements for economic production and social reproduction. Lefebvre suggests that the production of space is essential to the inner workings of the political economy.

-Lefebvre emphasized the importance of space for shaping social reproduction. One of the consistent ways to limit the economic and political rights of groups has been to constrain social reproduction by limiting access to space.

-Examples:

Exclusion of Japaness Americans from a residential neighbourhood in Hollywood, California

Male and female students sitting separately at a lecture on physics, University of Michigan School, late 1880s

Male and female students sitting separately at a lecture on physics, University of Michigan School, late 1880s

Cognitive maps of Los Angeles as perceived by predominantly Anglo American residents of Westwood, predominantly African American residents of Avalon, predominantly Latino American residents of Boyle Heights (The Visual Environment of Los Angeles, Los Angeles Department of City Planning, April 1971, pp.9-10)

Cognitive maps of Los Angeles as perceived by predominantly Anglo American residents of Westwood, predominantly African American residents of Avalon, predominantly Latino American residents of Boyle Heights (The Visual Environment of Los Angeles, Los Angeles Department of City Planning, April 1971, pp.9-10)-「職工盟帶過天水圍街坊”出城”,發覺她們連幾條主要隧道的名字都不知道。在文化認同上,她們只是一個” 天水圍人”,不是”香港人”」(陳惜姿﹕《天水圍12師奶》,頁159)

-Questions: how cultural identity and cultural politics of identity are constructed and shaped through the creation of meanings in place? Is it possible to intervene the cultural politics of identity through the production and technology of place?Through the preservation or constitution of social/public memories.

-One of the ways in which memories are constituted is through the production of place. Monuments, museums, the preservation of particular buildings and the promotion of whole urban neighbourhoods as “heritage zones” are all examples of the placing of memory. The very materiality of a place suggests that memory is inscribed in the landscape as public memory. Place is the realm of history-in-place.

2. Vietnam Veteran's Memorial(1982) by Maya Ying Lin (林瓔):

(Reference- Maya Ying Lin, Boundaries; Freida Lee Mock, Maya Lin - A Strong Clear Vision (DVD, 1995))

- Although administered under National Parks Service of the Federal Government, VVM was built in 1982 through the impetus of a group of Vietnam Veterans, who raised the funds and negotiated for a site on the National Mall in Washington.

-Situated on the grassy slope of the Constitutional Gardens nears the Lincoln Memorial, the memorial consists of two polished black walls of granite set into the earth at an angle of 125 degrees. The walls form an extended V almost 500 feet in length, tapering in both directions from a height of approximately ten feet at the central hinge. These walls inscribed with 58132 names of men and women who died in the war. The framing dates of 1959 and 1975 are the only dates listed on the wall; the names are listed alphabetically within each “casualty day”, though those dates are not noted.

-Virtually all of the national memorials and monuments in Washington are made of white stone and are constructed to be seen from a distance. In contrast, the VVM cuts into the sloping earth: it is not visible until one is almost upon it. The walls reflect the Washington Monument and the face of the Lincoln Memorial, but they are not visible from the base of either of those structures.

-Before it was built, the memorial was seen by many veterans and critics of modernism as yet another abstract modernist work that the public would find difficult to interpret. But they simply ignored fundamental aspects of this wall. It is not simply a flat, black, abstract wall: it is a wall inscribed with names. When the public visits this memorial, they do not go to see long walls cut into earth but to see the names of those whole lives were lost in the war. Hence, to call this a modernist work is to privilege a formalist reading of its design and to negate its commemorative and textual functions. While modernism in sculpture has been defined as a kind of “site-less-ness,” the memorial is specially situated within the national context of the Mall: the black walls mirror not only the faces of viewers but also the Washington obelisk, thus forming a pastiche of monuments.

-Before it was built, the design of the memorial was under attack not only because of its modernist aesthetics but because it violated implicit taboos about the remembrance of wars. When its design was first unveiled, it was condemned as a highly political statement, a monument to defeat. One Veteran of VVMF read it black walls as evoking “shame, sorrow, degradation of all races”; others perceived its refusal to rise above the earth as indicative of defeat.

-The primary aspect of the memorial that is responsible for the accusation that it does not appropriately remember war is its antiphallic presence. By “antiphallic”I do not mean to imply that the memorial is somehow a passive or feminine form but rather that it opposes the codes of vertical monuments symbolizing power and honour. The memorial does not stand erect above the earth, it is continuous with the earth. The shape of V has been interpreted as V for Vietnam, victim, victory, veteran, violate, valor. Yet, one also finds here a subtext in which the memorial implicitly evokes castration. The V has been read as a female V, reminding us that a “gash”is not only a wound but slang for the female genitals. To its critics it symbolizes the open, castrated wound of this country’s venture into an unsuccessful war.

-At the time the designer of the memorial was chosen anonymously by a group of eight male experts, Maya Lin was a twenty-one-year-old undergraduate at Yale University. She was not only young and incredential, but Chinese-American and, most importantly, female. Eventually, Lin was defined not as American but as “other”. The otherness became an issue not only in the way she was perceived in the media and by some of the veterans, it became a critical issue of whether or not that otherness had informed the design itself

-Trouble between Maya Lin and the veterans began almost immediately. The initial response to Lin’s design was so divided that it eventually became clear to the veterans of the MF that they had either to compromise or to postpone the project. At the end, a plan was devised to erect an alternative statue and flag close to the walls of the memorial, and realist sculptor Frederick Hart was chosen to design it. It was erected in 1984, consists of 3 solders – one black and two white – standing and looking in the general direction of the wall.

- The Name: the chronological listing of names on the VVM provides it with a narrative framework. Read chronologically, the names chart the story of the war. As the names listed alphabetically within a casualty day swells, the intensity of the war is told.

-The incommunicability of the experience of the Vietnam War has been a primary narrative in the Vietnam veterans’discourse. It was precisely this incommunicability that rendered the construction of the VVM necessary. It was due to the fact that, the veterans had been invisible and without voice before the VVM’s construction and the subsequent interest in discussion of the war. Unlike WWII veterans, Vietnam veterans did not arrive home en masse for a celebration but one by one, without any welcome. They were marginalized in the society.

-Within the veterans’ community another group is struggling against an imposed silence: the women veterans. Upon their return, these women were not only subject to the same difficulties as the veterans but were also excluded from the veteran community. Thus, several of these women raised funds to place an intentionally apolitical statue of a woman near the VVM. In August 1990, a design competition for the memorial, to be located just south of the wall, was announced. It’s Hart’s statue that the absence of women so visible make them initiate the project.

- The VVM has been the subject of an extraordinary outpouring of sentiment since it was built. It is presently the most visited site on the Washington Mall. The memorial has taken on all of the trappings of a religious shrine – people bring personal artefacts to leave at the wall as offering. This rush to embrace the memorial as a cultural symbol reveals not only the relief of voicing a history that has been taboo but also a desire to re-inscribe that history. To the veterans, the wall is an atonement for their treatment since the war; to the families and friends of those who died, it is an official recognition of their sorrow and an opportunity to express a grief that was not previously sanctioned; to the others, it is either a profound antiwar statement or an opportunity to rewrite the history of the war to make it fit more neatly into the master narrative of American imperialism. The Memorial’s popularity must thus be seen as an integral component of the recently emerged Vietnam War nostalgia industry. (it transform guilt into duty and pride)

-As the healing process of the Vietnam War is transformed into spectacle and commodity, a complex nostalgia industry has grown.

- The National Park Service is now compiling an archive of the materials left at VVM. Originally, the Park Service classified the objects as “lost and found”. Later, it realized that the objects had been left intentionally, and they began to save them. The objects thus moved from the cultural status of being “lost”to historical artefacts.

- The subject of memorial is not limited to Vietnam War, the objects related to issues such as AIDS, homosexual, Gulf War had also been left at VVM.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home